Overview of collaborative art projects

The art that I am interested in making arises from interests that do not avoid the conflict of the growing individualization of modern societies, but rather confront and expose it, opening ourselves to the critical experience of being together, although at times this could be rare, elusive or even upsetting. Therefore, it can contribute to reveal the secrecy that sometimes separates contemporary art from the public and, at the same time, experiences can be developed allowing progress in the opposite direction to the dehumanization and fragmentation, so characteristics of our time.

I seek to point out the fragile and diffuse border between what is considered our own and what is strange, between the self and the other and, finally, between them and us. Eduardo Galeano described it better: “From the Mayan language we learned that there is no hierarchy that separates the subject from the object because I drink the water that drinks me and I’m looked by everything I look at, and we learned to greet like this: I am another you, you are another me.”

_______

The act of walking

Certain areas in the south of Mexico City are typically known for being lake lands. Ancient canals and lakes where pre-hispanic cultures developed the agricultural system called chinampa, which consists on the creation of a giant raft on the water, with a frame made of logs, on which soil is placed along with easily decay materials such as grass, litter, vegetables and others.

This area was recognized for being the great garden of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, city of the Aztecs or Mexicas, who used the water canals to transport the agricultural products that were harvested and took them through chalupas (small boats) to the large markets of the center of the city. From the conquest of Mexico, the Spanish rulers of Mexico City dedicated themselves to drying up lakes and canals. This mindset of conceiving water as an enemy of progress and not as a fundamental ally of civilization, continued for many centuries until 1966 when the last rivers and canals of Mexico City were piped. Thus ending, in a sense, with the pre-hispanic lake city. Peter Krieger, an art historian, explains it like this:

Throughout the history of the city, the dominance of natural forces served as a metaphor of political power. Controlling the anarchic flow of water, especially in Mexico, where there are frequent floods, it also meant ruling over the urban population and distributing it through the organized spaces of the city.

These conditions related to urban planning and public space have had different types of influence on art and cultural creation. Many artists feel a passion for the urban environment, for its streets, we are walkers, or as Walter Benjamin would say: flaneurs, urban explorers, a kind of naturalists who walk through cities rediscovering their ecosystem, making it our object of study and lab for experimentation. Immersed in this spirit, on May 31st 2015, I began a walk from the south lake area of Mexico City, to the historic downtown, walking through streets that were formerly water canals. With this action I sought to symbolically relate the past with the present and perhaps also to be able to discover some clues or traces of the ancient lake city. 7 hours of walking in total, 22 km. Steps create bridges between historical periods, between places and between ways of understanding the world.

When I got to the city center, I was struck by finding a quarry bridge in the middle of a public square. This bridge seemed to have no reason to exist, I found it in the middle of a concrete slab, no water passed under it or any ditch, it simply lived camouflaged among hundreds of people who walked by and did not seem to notice its unusual presence. This image was engraved in my memory. Please remember it too, because we will return to it later.

Finally the walk took me to the heart of the city, to the site where the ancient mexicas found the promised sign by their gods: an eagle perched on a cactus, here they founded their city. They had left approximately in the year 1111 of our era, from the city of Aztlán, whose location is currently unknown, and had traveled through different regions of the current mexican territory until in the year 1325 where they found the sign in an islet that was in the center of a large lake. In this spot, they founded their city, Mexico Tenochtitlan, which became a great empire. And here I was standing now, hundreds of years later among cars, pollution, rivers of people and fast food restaurants.

_______

Starbuckstlan

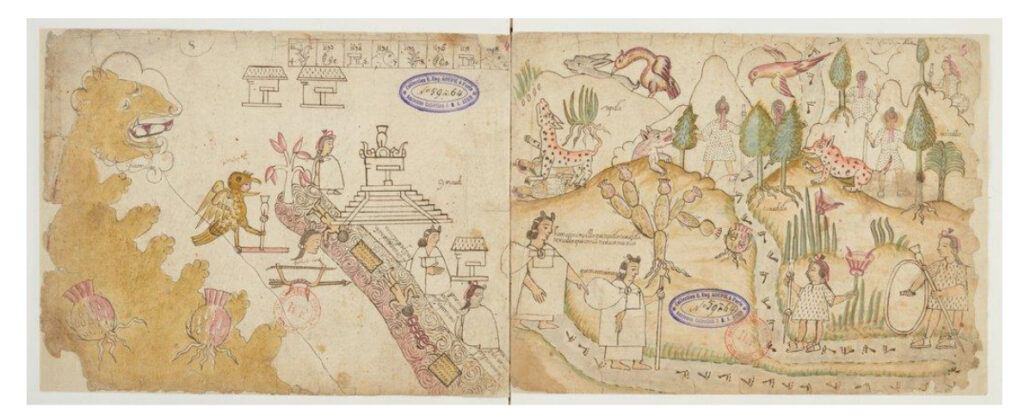

The journey that the Mexicas would take for several years was recorded in multiple pre-hispanic codex, although the vast majority of these were burned during the conquest and the colonial periods. Fortunately, a few of the codex that narrate this foundational migration are preserved today as they were made by indigenous artists during the viceroyalty period at the direct request of certain high-ranking spaniards, and that was how they managed to be saved from the great fire.

One of these codex is currently preserved in the National Library of France, located in Paris, and was named as the Azcatitlan Codex by the anthropologist Robert H. Barlow. The exact date of its creation is unknown but it must have been a few years after the Spanish, along with their allies, defeated the Mexicas (that is, after 1525). In this document, from folio 2 to 25, the scribe recounts the migration of the Mexica tribes. That is why this codex and others are very important to my culture, because they tell the foundation of our society. As you may know, the flag of my country represents this original event: the eagle perched on a cactus. The serpent that has the eagle in its beak was later added by the Spanish to represent the triumph of Catholicism (the eagle) over paganism and sin (the serpent). This syncretism is the foundation of our people.

Azcatitlan Codex

Taking the Azcatitlan Codex as a reference, I decided to develop a work that could help us understand, in the current context of globalization and neoliberal capitalism, how the migration of the Mexicas occurred. In a chaotic ultra-miscegenation environment such as the contemporary one, this codex would perhaps collaborate with the intention of giving meaning to our present. As the old saying goes: “To know who you are and where you are going, it is important to know where you come from.”

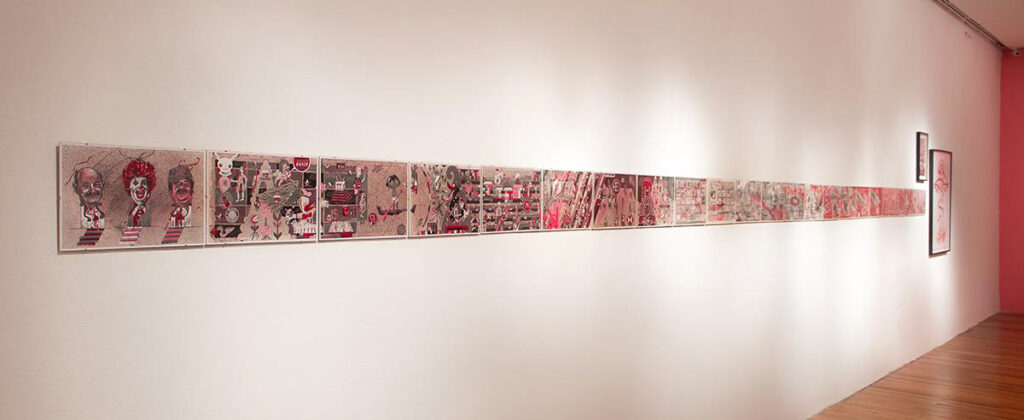

The Starbuckstlan Codex generates a space for reflection around the foundation of centralist power in Mexico, from a point of view related to mythical, historical, economic and political aspects. This work is made up of a graphic series consisting of 22 sheets joined together like an accordion. For its construction, I used kraft paper, made by hand, very close to the amate paper used by the Mexicas to make their original codex. In the same way, I used the dye that is extracted from the cochineal grana, an insect that is hemipterous and parasitic on cactus, as a red color, in the same way that it was used in pre-hispanic times. Along with these elements I added acrylic paint to obtain other colors, but above all, so that the use of these different materials meant a metaphor about the clash of cultures, about this time of ultra-miscegenation that I am interested in representing. Therefore, one of the two senses of mix of this project has to do with the encounter of these graphic materials, which belong to two opposite views of the world: one established in a more harmonious terms with nature and another which is part of the vision of human being’s dominion over it. The natural tint is opposed to industrial acrylic.

Cochineal grana stain and acrylic paint on craft paper (Vista Hermosa Paper, Oaxaca), 22 sheets.

Starbuckstlan Codex fragment.

Regarding the representations that can be found in the codex, I would like to say that since the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) implemented in 1994, our country opened the doors to the most powerful nation in the world (¿is it still the most powerful nation in the world?), our neighbors of the north, so that they would introduce, in a massive way, commercial products. These products are the force of consumerism, they are identified as icons of North American popular culture, expressed through cinema, entertainment, food, fashion and propaganda. They are pop icons of the American dream.

Based on this scenario, the Starbuckstlan Codex was created from questions such as: In what way does the free market today condition what we understand as our own culture? How can we interpret the founding stories of our society differently? In this tension between north and south, the United States of America-Mexico, traditional-industrial, the borders are situations that separate and communicate at the same time. How are global industrial traditions and practices currently converging? Their relationship is not one of simple opposition, but of multiple tensions. Nor is there a “reconciled universal coexistence”, that is, it doesn’t mean that the modern has eaten up the traditional and we are all happy about it, nor is it that we can remain permanently indisposed to the development of culture, technology and science. Starbuckstlan proposes a possibility in research on the cultural configuration of foundational myths in times of globalization.

_______

Six shared meals

Some time after having crossed this place for the first time, I found that it is called Plaza de la Alhóndiga (Alhondiga square). I visited it again several times to get to know it better and I realized that it’s a place where various products and services are marketed, legally and illegally: handbags, baby clothes, food, massages, miracle drugs and more. But above all, it is a place where its users eat, rest, chill and walk. In the same way, in this environment a diverse group of sex workers offer their services, however this activity is not evident since they do not show their bodies or dress differently from the rest of the users of the square. Also, some people living on the streets use the square as a recreational space, to consume drugs and to spend the night.

My initial encounter with the sex workers in the plaza was accidental. My original idea was to create a series of ephemeral installations in this public space that would help to show the importance that the water canal had long ago. However, as soon as I started working there, several people approached and voluntarily began to help me with my task. This is how things work in certain areas of Mexico City and the rest of the country, people are supportive and help you.

Johnny Walker, nickname for a very kind man who lives on the street and who later became an important part of the project, told me the day we met: “You are doing a performance here and you want to say something with all this, do you? Yes or no?.” And so it was. After some work sessions I understood that the focus of the project had to change and that I had to abandon the idea of installing things in the urban environment, because the importance of this space lay with the people who give it life every day.

Days later I returned to the Alhóndiga bridge with a picnic tablecloth and four kilos of tortillas. I put the tablecloth on the floor, sat down, and waited. Soon after, María approached me and said: “They already told me that you are an artist and I am the alcoholic queen. Make me a portrait”. Shortly afterwards, a large group of girls gathered contributing different foods bought in the neighbor locals under the argument that tortillas by themselves are not of much use.

Our picnic had been organized in an unexpected way. We ate and talked for a long time. The girls shared some personal stories that were testimony to their strength and their conviction to succeed despite adversity. I suggested that I could come back with some guests once a week and that we could organize this activity repeatedly. They agreed and we established that we would cook and eat in that same space, preferably on Sundays because it is their day off. The six shared meals had begun.

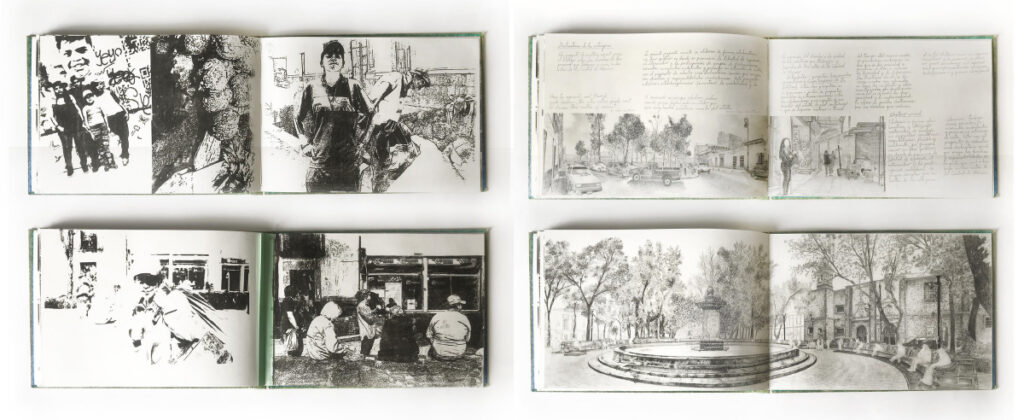

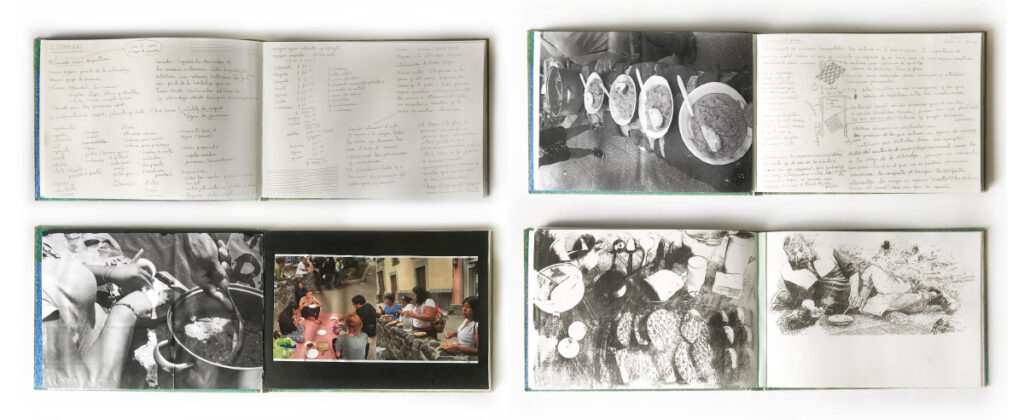

Six shared meals project notebook

The premise was simple: we were looking to create a space that was as horizontal as possible for coexistence and exchange as well as to activate a series of collaborative actions that pointed towards a common goal. Create public dynamics within a plaza whose purpose was not the accumulation of economic capital. The exchange of experiences and the learning that was generated, from cooking and sharing the space collectively, was the significant result. Why do I call this practice collaborative art? Because the activities that are decided to carry out are not determined by the figure of the artist, but rather she or he performs as a mediator so that different events can be carried out. The idea is that eventually this can be executed without an external organizer, but at the beginning, cooking and sharing food was a collective initiative and my task was to promote the administration.

The six shared meals would take place over six consecutive sundays, the menu would be proposed by the participants of the initiative and the ingredients would be assigned collectively in such a way that everyone participated in the preparation of the food so that everyone could enjoy it. In other initiatives, the artists have determined, so to speak, the rules of the game and the people who participate can act within certain established limits such as carrying out some activity, organizing a certain game or establishing a specific dialogue, but what makes this particular project significant is that all the decisions were decided together, in order to serve a common good. If the interests served within the project were solely those of the artist, the collaborators would loose interest and would stop voluntarily attending the meetings. What is ephemerally built here are a series of benefits that point in multiple directions.

In the words of the art historian Karina Ruiz:

The urban environment was conceived as a place of exploration, discovery and restitution of the social function of a public square, under the premise “we all cook, we all eat”. The project arose from the tracing of a route that indicates the historical importance of a site and the random encounter with people who inhabit it in the present; young men and women, of middle and advanced age, who use their sidewalks and corners to seek support, sleep, drink alcohol and consume narcotics. Santiago Robles managed to insert himself in the space, fostering a new interrelation of subjectivities and diverse experiences around the realization of a collective, extra-everyday and informal activity. Six shared meals is read as an experiment of social articulation, community, exchange and roots, in a place where, either you are passing through or you live in precarious conditions.

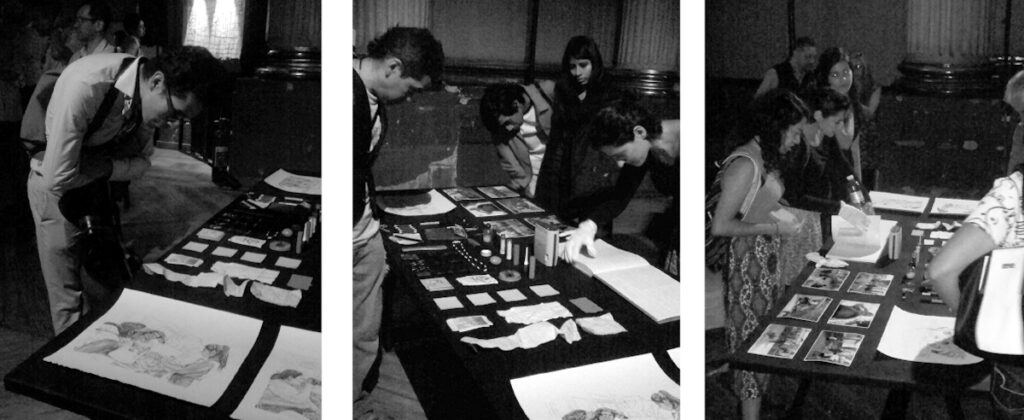

The final phase of the project took place during an event at the Ex Teresa Arte Actual Museum, which is very close to the Plaza de la Alhóndiga, in which te power of listening was reactivated and diversity was valued. The collaborators of the project attended this event and in a respectful space, shared their experiences with a wide audience that was highly interested in what had happened and asked many questions and shared their points of view as well. The events that happened at the six shared meals were translated into different formats within the exhibition space: chronicles, photographs, collages, drawings, audios and pieces produced in a collaborative way. However, the work is intangible. What was exhibited were only records of a process of intersections of consciences, of life stories.

_______

Transition zones

After developing a series of initiatives that took place in the Historic Center of Mexico City, I had the need to turn to see other spaces and other circumstances, to decentralize myself in a certain way.

I cultivated a desire to know with respect and interest, through a pedestrian rhythm, the transition zones (limits between urban and rural) of some cities, to know the diversity they harbor and, therefore, stop considering the other, what is out there in unknown territories, as foreign to us. What is the meaning of this proposal? Currently, private and commercial areas are what define the organization of cities. This causes that as citizens we know very little about the urban territory: we always travel through the same places, we live with similar people, we shop in identical spots. Routines give us a kind of security — we feel safe in our comfort zone. However, it’s a condition that at the same time as this brings us closer to certain areas, it isolates us from many others. Our life in big cities is individualistic and fragmentary.

So, letting myself go freely through long walks in order to better understand the relationship of tension between the urban and the rural was very nurturing for my creative processes. I started this project before the global Covid-19 pandemic but throughout it, the project acquired many new meanings. Now that we miss nature so much and that our relationship with it has become more distant than before, since we cannot go out, then my bond with nature has been based on the records I took from these walks. In other words, for me, nature became now a kind of techno-nature, a rural environment that could only exist in photographs, videos, audios and digital maps.

Cuando tenía 5 años todo esto estaba sumergido en agua. 2020

Toda esa orilla era el lago. Dyptic. 2019

Esta calle es tuya. 2020

Flores de agua. 2020

The most representatitive works of this project portray elements of the transitions zones of one of the cities that for several centuries was the second most important in Mexico: the city of Puebla. The outskirts of this me megalopolis, located in the central part of Mexico, is mostly an agricultural space with strong social inequalities. One of these areas, which is of great importance due to the natural resources it has, is the Atoyac River, which flows into a dam that makes it the largest body of water in the state. The sustainability of the place is threatened by the type of use they make of the land and water and by the imminent growth of the city. #RiveradelAtoyac and #Zopilotl aim to show how the events found in this environment can become images prone to be massively consumed. These works refer to the cultural tools built by the peripheral communities of the cities as well as the market opportunity that precariousness in terms of exoticism can cause when they are shared through social networks. #RiveradelAtoyac represents a boat built in an improvised way, with natural and waste elements, which the inhabitants of the area use it as a public vehicle to be able to cross the river. For its part, the #Zopilotl is the materialized dream of a construction in the middle of nowhere that was never finished, which remained as a portal, as a sign for the surprised walkers who find it in their path. The Zopilotl is a large scavenger bird that in these environments feeds on garbage, which we can see perched on top of this great wall that perhaps could not be finished because remittances from the United States of America stopped reaching the family.

Left: #Zopilotl #Portal #Mextagram #Instatravel #Viajandoando, 2021 / Right: #RiveradelAtoyac #TropicalVibes #RiseAndShine #PlacesToGo #FilterFun, 2020

Oil on canvas

In the words of Christian Barragán, curator and art teacher:

Among the multidisciplinary projects undertaken by Santiago Robles in the last five years, Zonas de transition stands out, as an exercise that mediates between art, the environment and the friction that the landscape provokes in human beings. Made up of walks, testimonies, chronicles and diverse visual documentation, Zonas de transition has also materialized in a new series of paintings that, from their titles, openly manifest a critical position regarding the facts that indicate: The city does not end here because we know that it does not it never ends, All that shore was the lake and When I was five years old, all this was submerged in water, they are just some of the works of this pictorial body.

Made from 2019 in a medium format, characteristic of the advertising poster, each of these paintings has the peculiarity of being founded on a historical and formal pun of art. While the technique used, oil on canvas, refers to certain ideals of classical painting, especially when addressing a genre as traditional as landscape, the palette selected by the artist based on neon colors and tones, typical of products and commercial brands, denotes an uncertain and volatile contemporary context alien to an illustrious past fixed in the imaginary of humanity. (End of quote)

The art historian Laura Martínez would complement:

With this project, again Santiago Robles establishes a fundamental question: what is our relationship with the environment?, and the series of responses are disturbing, comforting, hopeful and realistic , everything at once. Nature dries up, withers, cuts and reproduces. We witness the endless death and resurrection of the vegetation around us, places that fallow, places that re-bloom, places that dry up and places where the water returns, with or without human consent. The artist remains an eyewitness, historian of the events, memory of destruction-rebirth as a perpetual cycle.

This peripheral and pedestrian proposition to leave our comfort zones is also close to what Guy Debord called psychogeography, which involves searching and detecting how the landscape influences our emotions and our way of perceiving reality —in this case, our conception of the idea of the city and its relationship with the rural—. An interest in knowing our cities today is promoted, not only that which we can find in the books that describe the “glorious” past of cities or the writings that seek to generate a theoretical model about them, but also go out, walk and meet head on with the great landscape that houses and identifies us. We are walking are inside the world, and as we walk, we remake its memory and our story.

_______

The chahuiztle has fallen on us!

Clarification: Chahuitztli is a prehispanic word that means “maize disease”, therefore, “The chahuiszle has fallen on us” is an old saying of popular domain that means that as a society a curse has fallen on us.

Maize, society, culture and history are inseparable. Our past and our present are based on maize. Our life is based on maize. We are maize people.

Guillermo Bonfil Batalla, anthropologist

This project seeks to promote a conversation around the effects of global biogenetic practices today, in both environmental and nutritional terms. The purchase and planting of genetically modified maize in the mexican context, where the diet is based mainly on the consumption of this grain, will have irreversible harmful consequences. On one hand, a native plant —since corn was originated and diversified mainly in Mexico— will permanently modify its gene pool, since there is no way to prevent the transgenes that are introduced from contaminating natural populations, because pollen travels through the air and fertilizes the female flowers. On the other hand, transgenic maize will make food production more expensive, since buying the seed year after year, instead of saving it as farmers have always done, will increase costs throughout the entire food chain.

¡Ya nos cayó el Chahuiztle! is part of a food, environmental and cultural project that promotes the sustainable planting of natural maize through a model of social alliance that starts from a loving and committed relationship with the land and its products. This project responds to the urgent need of the mexican people to wake up and warn that maize, the primary basis of daily sustenance, is being strongly threatened by industrial and corporate advancement.

The neoliberal capitalist model makes the consumption of maize an act that puts individual health at risk and the preservation of the ecosystems where its extensive plantations are developed, putting the traditional cultivation at risk and deepening, at the same time, the inequality and marginality of indigenous groups of the country, to whom this ancestral heritage is owed. In contrast, the conscious consumption of creole maize, of traditional milpa, would reactivate national production and promote the valuation of its cultivation as a dignified and prodigious work, embedded in the bases of the material and spiritual identity of the people.

Commercial brands use transgenic maize (mainly in the form of syrup) as part of the ingredients of their edible products, although this is not essential for its preparation. This responds to an economic logic that is superimposed on nutritional needs.

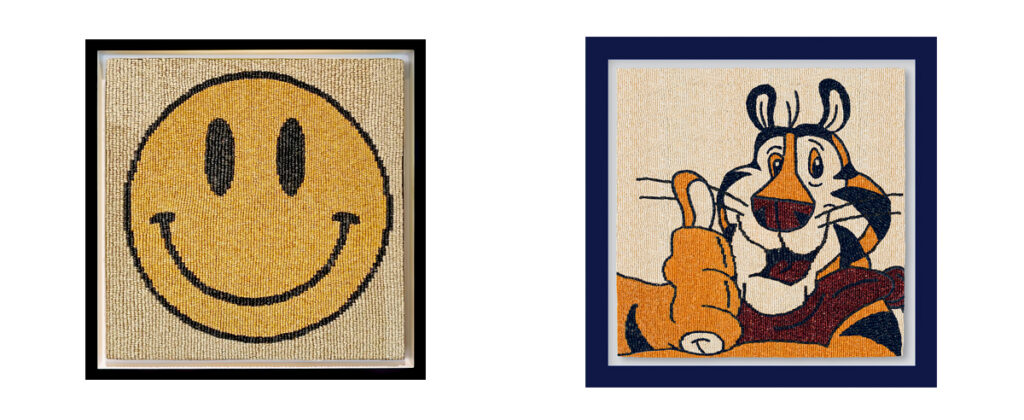

Genetically modified corn is consumed mainly in the form of ultra-processed foods, such as chips, beers and soft drinks which in certain rural areas of Mexico are more accessible than drinking water. The artistic works that are created for the series ‘¡Ya nos cayó el Chahuiztle!’ are built from the assembly of thousands of seeds in each piece. Sections of the works are chemically protected and others are not so that over time, the piece will consume itself due to the interference of insects that feed on maize. This process would take several years.

All ways, more than 34 000 seeds of hybrid maize

With these works made with hybrid and genetically modified seeds, the traditional planting of native corn is promoted in Amatlán de Quetzalcóatl, in the state of Morelos of the Mexican Republic, a population of farmers that has its origin in pre-hispanic times and that at the end of the last century gradually abandoned the traditional sowing model to start using agrochemicals, pesticides, hybrid maize seeds and polluting machinery. This artistic-environmental project seeks to reverse this process and demonstrate that the traditional and natural way is not only sustainable in economic terms, but will also allow the recovery of an ancient cultural tradition of respect for nature: healthy food for a healthy body and mind.

Left: Happy Meal, 2021 / Right: Tecuani, 2021

Left: Lies, 2019 / Right: Colonialismo extra, 2021

—————————-

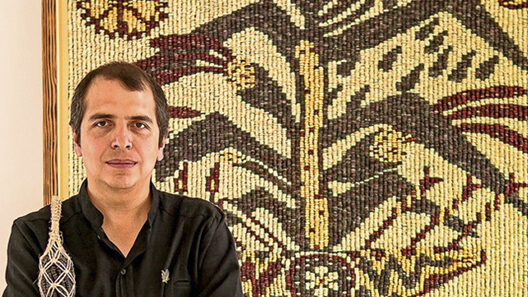

Santiago Robles. Master in visual arts from the Faculty of Arts and Design UNAM, studied at the Art Students League in New York and at the Clinics for the Specialization in Contemporary Art in Oaxaca, UABJO-La Curtiduría Cultural Center. He was a fellow of the Program Young Creators (2015-2016) in the graphics category. On two occasions he has been an adjudicating jury and tutor of the Program to Stimulate Artistic Creation and Development (PECDA) in the visual arts category. He has published the books of his visual art work Migración (2019), Codice Starbuckstlán (SARA, 2020) and We all cook, we all eat. Collaborative art projects in the public space of Mexico City (2021). He has presented solo and collective exhibitions in countries such as France, Austria, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Brazil, Iran, Colombia, Cuba, the United States of America and South Korea. His work is promoted by Saisho Art and Diderot Art.